Meeting in the Middle: Two Forms of Equine Uveitis

Diseases of the middle layer of the eye, the uvea, are among the most common ocular conditions in horses. Depending on the disease severity and duration, vision can be significantly compromised. For this reason, regular eye examinations are an essential part of routine care.

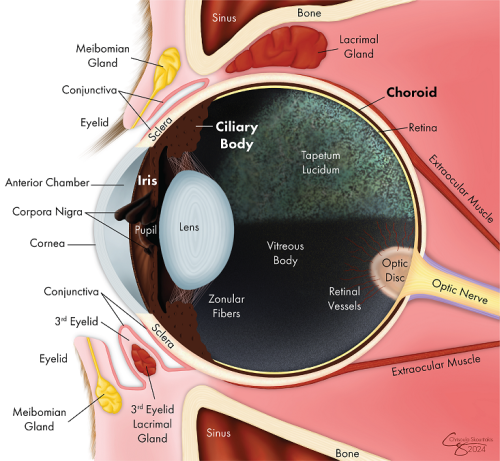

Inflammation of the uvea (iris, ciliary body, and choroid) is known as uveitis. It can occur once, such as with trauma or infection, and never again. Other forms are caused by an immune-mediated response to a systemic infection, autoimmune disease, or other triggers and may be chronic or recurring.

The most common form of uveitis in horses is equine recurrent uveitis (ERU). Recently, another form has been documented, heterochromic iridocyclitis with secondary keratitis (HIK).

Equine recurrent uveitis

Equine recurrent uveitis (ERU), or moon blindness, is the most common cause of blindness in horses worldwide. It affects 2 - 25% of horses globally, with 56% becoming blind. There is no cure for ERU.

During an episode, horses may be painful and exhibit clouding of the cornea, tearing, squinting, and redness, which can increase in severity with repeated occurrences. A subclinical form, insidious uveitis, consists of a constant, low level of inflammation that causes cumulative damage to the eye, but is not outwardly painful. The absence of outward signs can cause severe vision damage before an issue is recognized. Cumulative damage caused by ERU can lead to cataracts, glaucoma, and blindness.

Enucleation

Despite the most advanced treatments, some horses require removal of one or both eyes (enucleation) for humane and medical reasons. It is important to acknowledge that ocular pain usually does not stop when vision is lost. For this reason, vision-impaired horses often show significant improvements in comfort after enucleation, which can also result in positive changes in temperament.

Enucleation is a common procedure, and the surgery is often performed in horses with standing sedation, as opposed to general anesthesia. This reduces costs, avoids anesthesia-associated complications, and is safer for older horses and those with certain medical conditions.

Environmental and management modifications may be required, and it is important to allow horses time to adjust after the surgery. Many partially, and even fully, blind horses adapt well, with many returning to a similar level of performance. Success ultimately involves many factors, with the horse’s temperament being one of the most significant variables.

Infectious organisms, particularly Leptospira, can trigger ERU, but genetic risk factors are also important. Appaloosas, draft breeds, and warmbloods are predisposed to ERU, but it can affect horses of any breed. Appaloosas are eight times more likely to develop ERU than other breeds and significantly more likely to become blind in one or both eyes. Researchers at the UC Davis Veterinary Genetics Laboratory were involved in the identification of LP, the allele causing the white leopard complex spotting pattern, as an ERU risk factor in the breed, with homozygotes (LP/LP) being at highest risk. Research into genetic factors that influence ERU risks in other breeds is ongoing.

Treatment for ERU focuses on eliminating or reducing inflammation in the eye(s), preserving vision, alleviating pain, and minimizing recurrence. Topical corticosteroids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can reduce inflammation and minimize damage during an active episode, but are not necessarily effective at preventing recurrence.

Severe or frequent flare-ups may require injections of medications directly into the eye(s) and/or the surgical placement of a cyclosporine implant, a sustained-release device that provides therapeutic dosages of cyclosporine for up to three years to control inflammation and minimize recurrences. Surgery to remove the eye (enucleation) is often recommended for ERU-affected eyes that are painful or have become blind (see box).

Heterochromic iridocyclitis with secondary keratitis

Uveitis is also one of the hallmarks of a more recently identified progressive ocular disease, heterochromic iridocyclitis with secondary keratitis (HIK). Like ERU, HIK is likely immune-mediated. Cases have been reported in a variety of breeds.

Affected animals can exhibit cloudy corneas and excessive tearing and blinking, similar to ERU. In fact, horses with HIK were often previously diagnosed with ERU. Distinct characteristics of HIK include pigmented cellular deposits on the inside of the cornea, thickening of parts of the cornea due to fluid accumulation, and the appearance of fibrous membranes behind the cornea. Clinical signs of HIK are progressive, but not episodic, as observed with classic ERU. As a result, the causes and processes of disease development are thought to be distinct for these conditions.

Like ERU, treatment for HIK consists of medication injections, cyclosporine implants and/or topical medications. Outcomes are variable and affected horses need frequent follow-up exam-inations and aggressive local immune suppression for disease control. There is no cure for HIK and cases that do not respond to therapy require enucleation to ensure long-term comfort.