A Scratch for Every Itch

Equine Skin Allergies

Horses scratch for many reasons. They scratch themselves on fences, rub up against posts (and sometimes people), roll on the ground, and groom each other. A natural behavior usually linked to social bonding, comfort, and relaxation, it can be heightened seasonally by shedding, sweating, or the presence of insects. However, when scratching becomes frequent enough to result in hair loss, broken skin, scabs, or disrupts eating or sleeping, it is time to talk to a veterinarian to determine if a skin allergy is to blame so appropriate treatments can be pursued.

Allergies are the result of immune reactions to proteins that the body identifies as foreign (allergens). They are often caused by repeated exposures to pollens, weeds, grasses, molds, insect bites, medications and feeds (although food allergies in herbivores are rare). Equine skin allergies typically cause abnormal itching (pruritus) and hives (urticaria).

Breaking Out In Hives

Among domestic animals, horses are the most likely species to be affected by hives. These raised, round patches on the skin are not a disease themselves. Rather, they are skin lesions or reaction patterns that result from certain diseases and conditions.

Frequent causes for hives in horses include:

■ Atopic dermatitis (environmental allergy: pollens, molds, etc)

■ Drugs and medications

■ Insect/mite bites or stings

■ Chemical contact (plants, dyes, detergents, soaps, insecticides, etc.)

Less common causes are:

■ Dermatophytes (ringworm)

■ Pemphigus foliaceus (auto-immune skin disease)

■ Stress

■ Vasculitis (including purpura hemorrhagica)

■ Pressure or trauma to the skin

■ Cold

■ Exercise

■ Feed

Hives typically appear suddenly and in large numbers. The most distinguishing characteristic is that they ‘pit’ if you put pressure on them. It is important to try to determine the underlying cause of hives by evaluating the horse’s medical history in order to provide proper treatment. A seasonal itch, for example, would be most consistent with atopic dermatitis to pollens, whereas an itch that persists year-round is more likely to be a reaction to molds, barn dust, or feed. Episodes of itching that occur after topical treatments of shampoos, dips, etc. would be consistent with a contact allergy.

Allergy Testing and Allergy Shots

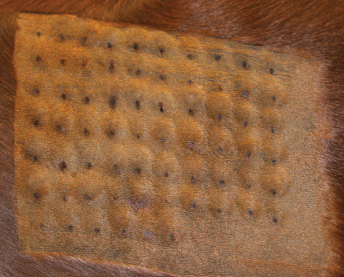

Intradermal tests (IDT) and serum (blood) allergy tests are often used to identify allergens responsible for hypersensitivity reactions. Similar to allergy tests in humans, IDT involves injecting extracts from pollens, molds, and other environmental substances into the skin (often in a grid pattern; see picture at right) and measuring injection site responses anywhere from 30 minutes to a few hours later. Serum (i.e. blood) allergy tests are not always in agreement with IDT. Studies have reported variable repeatability for either method across time and individual animals, which could be due to a variety of factors. Horses with atopic dermatitis and recurrent hives generally have a higher incidence of positive reactions than healthy horses.

Allergens identified as causing hypersensitivity reactions, and interpreted in light of the horse’s known disease history, clinical signs, and elimination of other causes, may then be used for hyposensitization therapy (also known as allergen specific immunotherapy (ASIT), or ‘allergy shots’). A study that evaluated treatment of cases of atopic dermatitis at the UC Davis veterinary hospital over 17 years noted an approximate 70% success rate in hyposensitization in horses; an analogous study at the University of Pennsylvania reported similar results. Interestingly, whether the hyposensitization is based on IDT or serum tests, the success rate is approximately the same. There is now the option of using oral hyposensitization instead of injections.

The ultimate success of this type of therapy depends on adherence to instructions set forth by the veterinarian. This includes anticipating that injections will need to be administered (usually by the owner or the horse’s caretaker) for at least a year, even if decreased clinical signs are observed within a shorter period. Approximately 85% of horses that respond to the therapy need continued hyposensitization for life, although often at decreased frequency.