Equine Rehabilitation

Personal Reflections from a UC Davis Veterinary Student

One year ago, I climbed aboard my 18-year-old hunter, George, and picked up a trot. My stomach sank almost immediately. He was obviously lame. As a then second-year UC Davis veterinary student, I knew from my studies that the potential explanations for his sudden lameness were endless, and panicking would not do any good. I gave him some Bute, a couple of days off, and hoped for the best. A week later, he looked almost back to normal on the ground; however, he still didn’t feel right under saddle.

UC Davis Field Service came out to our barn to examine him. Radiographs and an ultrasound found nothing. The pain blocked to his foot, so he was brought to the UC Davis veterinary hospital’s Large Animal Clinic for a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. The MRI showed moderate inflammation of the lateral collateral ligament (desmitis) in his left front coffin joint.

All that I could think about was learning what I could do to help him recover, what the prognosis was, and if he would ever be the same jumping horse he was before the injury. I received mixed answers - from being told that he would never be able to jump again to anticipation of a full recovery with proper treatment and rehabilitation. Under the advice of experts in the UC Davis Equine Surgery and Lameness Service, Equine Field Service, and Equine Sports Medicine teams, we proceeded with shockwave therapy, shoeing alterations, and two months of stall rest, with 15 minutes of walking daily.

The beginning months of rehabilitation were the most difficult for both me and George. It was incredibly hard to limit his activity so significantly since he was a fit show horse and was clearly not a fan of the approach. He’s a big horse with a big personality, and in those early days, taking him out of his stall was an adventure. There was always a chance that he would try to bolt and take off (with occasional success). At the two month mark, we were able to start trotting in straight lines under saddle, which definitely made things easier. The rehabilitation process continued to get easier as his work increased over the next six months.

The entire eight month rehabilitation process was one of the most difficult things I have experienced. It was a challenge balancing what I knew was the right thing to do medically and making sure my horse was happy enough to want to keep going. There were especially frustrating times when none of it seemed worth it.

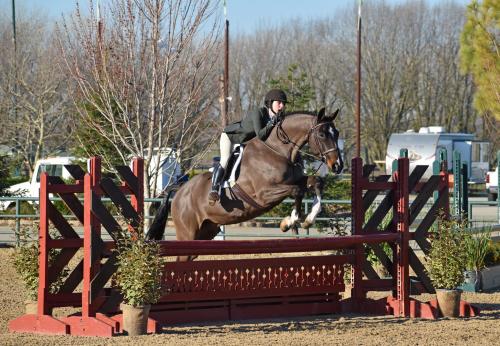

Now, one year later, I’m thrilled to be able to say that all of the hard work paid off and George is back doing what he loves to do. He is turning twenty soon and is completely sound, competing at the same level that he was before his injury.

The UC Davis veterinary team played a vital role in George’s diagnosis and recovery. His case was part of a research study using positron emission tomography (PET) scanning, pioneered in the horse at UC Davis, which determined exactly where the inflammation was in his foot and allowed for localized treatment and individualized rehabilitation. I owe George’s recovery to the UC Davis veterinary team. I do not know where we would be today without their knowledge and guidance.

I plan to pursue a career in equine sports medicine and/or advanced imaging, the veterinary specialties that played the greatest role in George’s diagnosis and recovery. Seeing firsthand their importance and what they are able to accomplish makes me excited to be able to help others the way that these fields of medicine helped George.